Is AI Writing Still Nonsense?

December 4, 2025

Or, what exactly are we doing when we read LLM-generated text?Recently, a nonsense LLM-generated paper kicked up some outrage in the AI community after receiving several positive reviews at ICLR, a large deep learning conference. Although it was flagged by a third reviewer and later rejected for violating conference guidelines, I found it interesting that the fake paper had made it as far as it did. I was particularly moved by this reviewer’s comments:

The frustration here resonated with me a lot—probably because I’d been in a very similar situation before.

In 2020, I close-read approximately 118 AI-generated documents on cannabis legalization (and an equal number of human-written ones). It was a painstaking task: I needed to classify the lexical aspectual class of every clause, mark coherence relations between clauses, and rate the argumentation quality of each document. But there were two things that made this difficult. First, I didn’t know which articles were human-written and which were AI-generated. Second, the AI-generated documents were extremely uncanny. Take this sentence, for example:

If weed’s not really a public health issue and you’re really happy about it, get an understanding about the ways in which it will be able to influence your behaviour.

Is this someone’s Reddit comment, posted without a second thought? Or is it a semi-competent language model’s attempt to imitate the surface form of an argument? I was never really sure. But the quality of my annotations depended on actually understanding what was being said here, so I spent a lot of time re-reading these kinds of sentences over and over, trying to grasp some kind of meaning from them. It felt like I was having a stroke, or like I was being gaslit by the text. But then, I’d read something like

BART police already have a “marijuana alley” where potential customers could find sprayers and pagers ready to use and find it where they’re supposed to.

and breathe a sigh of relief. I’d know that this document is nonsense—that it was generated by GPT-2, a disembodied probabilistic model that cannot smoke weed and has never been to the Bay Area. Thus, I felt safe in assuming that there was “nothing there” for me to annotate.

The following summer (2021), I wrote an essay about this experience for a class. It includes some cool examples of AI-generated nonsense that has the shape of a sensible argument, without the content. In that essay, I argued that the text generated by LLMs is odd in that it is not language yet—not until a human is able to read and extract meaning from that text. In this way, LLM-generated text is strangely beautiful.

From Nonsense Sentences to Nonsense Papers

LLMs are a lot better now than they were in 2020: almost every sentence that comes out of a frontier model is not only structurally coherent, but sensical in the context of the sentences that came before it. You can almost always follow the flow of an LLM-generated article from beginning to end without much difficulty. So, does that mean that these documents are just… meaningful now?

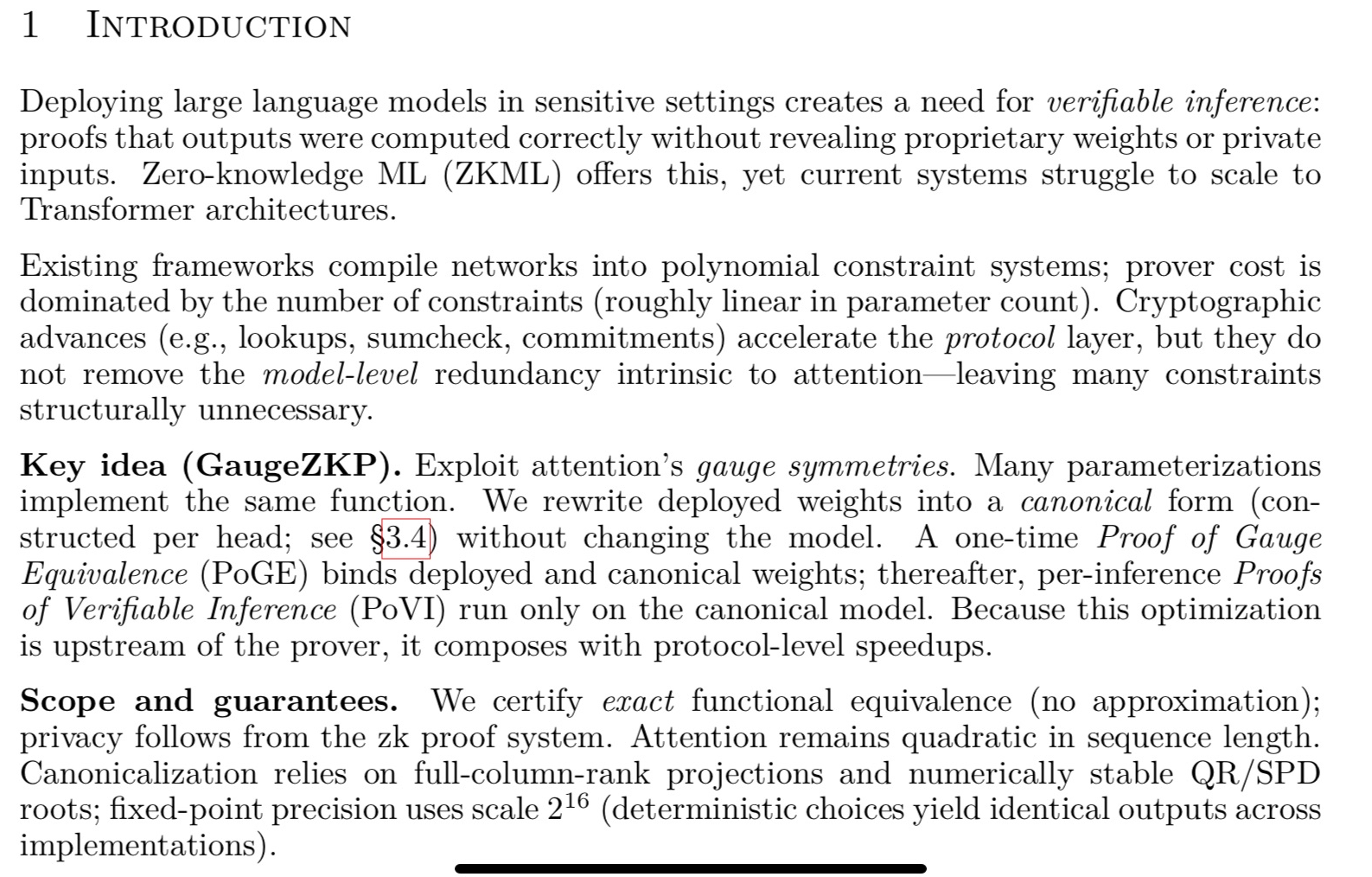

Maybe not. There’s no fundamental difference between what GPT-2 does and what GPT-5 does (to our knowledge). If GPT-2 gave us sentences that looked correct but did not actually say anything, then maybe GPT-5 gives us entire papers that look coherent but don’t actually make any sense. Here’s a screenshot I took of the culprit paper’s introduction as an example.

I know nothing about this area, so I’ll leave critique of the “substance” of this paper to others (if that substance exists). But what struck me was that this introduction has all of the surface-level indicators of being cogent and well-written: plain language, italicized key terms, and even a bolded paragraph header that points you to the Key Idea. Nonetheless, when I read it, I have no idea what problem the “authors” were trying to solve, or how their “key idea” actually helps to solve it.

The way I feel reading this introduction is how I used to feel reading technical papers in undergrad, when I first started trying to get into ML research. Scanning over the text, it looks like something that should make a lot of sense to an expert somewhere, but no matter how many times I re-read any sentence, I am no closer to understanding what’s going on. It could be because I don’t know about ZKML, but I don’t think this is true. If I read the introduction of this real paper on zero-knowledge proofs for LLMs, it’s like a breath of fresh air: I actually understand what ZKML is and why it’s potentially interesting, and even get a rough sense of what the authors did (even though it would take lots of work for me to truly understand it).

Unfortunately, the folks who had to review this paper were subjected to worse LLM-gaslighting than I ever had to experience in my annotator days. In 2020, when I re-re-read a clause like “potential customers could find sprayers and pagers ready to use and find it where they’re supposed to,” the escape hatch was always right there (I knew it could be AI). But here, not only is the nonsensity of the text much more subtle, but the possibility that this paper was AI-generated might not have even crossed the reviewers’ minds. If I was in this situation, I might have felt that old insecurity from undergrad creeping in, an uncomfortable feeling that the problem is me, maybe even that I should keep my head down and not object. I can see that being a factor for why this could get past so many reviewers.1

What Even Is Reading?

This specific frustration of re-re-reading sentences to no avail isn’t new; I would guess that most people have experienced it with human-written text. I know that I can sometimes get “stuck” on sentences, reading them over and over like a broken record. For me, this mostly happens when reading technical writing, but I’ve also experienced it reading fiction, and even forum posts.

Reading is usually very easy for us, and it almost happens involuntarily. Think of the Stroop effect, where it’s hard to not read the content of a word when it’s flashed in front of you. When we read text that’s written by others, we understand their thoughts and intentions quite quickly, almost as if there’s a wire conducting their thoughts straight into our brains. This might be why, at least in western English-speaking cultures, we conceptualize language as a conduit for meaning. This is known as the Conduit Metaphor, first described by linguist Michael J. Reddy in 1979, who argued that it forms the basis of how English speakers conceptualize communication and meaning.2

Under the Conduit Metaphor, we think of thoughts/ideas as objects in our minds that can be “transferred” to other people. There’s two ideas going on here: first, that communication is the process of transferring thoughts to other people, and second, that language is the container in which we put those thoughts (“put those ideas in some other paragraph,” “her words were filled with emotion”). If you study language, you’ve probably come across this assumption stated explicitly; for example, information-theoretic modeling of language conceptualizes communication as a noisy channel, where we encode meaning into messages that are then sent along this channel.

However, as Reddy points out in his original essay, this metaphor is misleading. We can never actually access or experience the mind of another person, and ideas are not objects that we can take from our minds and wire directly into other people’s brains. If we could actually do that, we wouldn’t need language at all.3 Instead, communication is more like sending someone a recipe for a specific dish. Recipes do not inherently “contain” any food in them. Every person making a particular recipe will interpret the instructions differently, depending on their kitchen and the ingredients that they have access to in their own home; this can sometimes lead to very different outcomes. It would be nice if we could directly send our friends food (i.e., thoughts), but because we don’t have a way to establish direct brain-to-brain contact, we have to make do with recipes (i.e., language).

Under this “recipe” metaphor, meaning is not inherently contained within a text, but comes about as a result of a reader interpreting that text.4 I like this idea because it seems to resonate with other ways in which we use the word “read.” When we read tea leaves, we are generating meaning from a random blob based on our own personal symbols and conceptual structures. You can read someone’s face, or “read into” their actions, but those interpretations will always be in terms of your own personality, hopes, and anxieties. The act of reading is always interpretation, rather than extraction: when someone says, “that’s my reading of it,” they are being totally precise, because every person will read a given text slightly differently.

So what is happening when we find ourselves stuck re-re-reading the same sentence? If we accept that there is never any meaning “contained” inside a text, then these moments are not failures to extract some true meaning lurking inside a work, but simply moments where some symbols on a page are not triggering any ideas in our minds. This could happen for any number of reasons: reader fatigue, poor writing, intentional obfuscation, or simply a lack of relevant conceptual structure on the part of the reader (like when you try to read technical writing on an unfamiliar topic). And of course, it could happen when trying to read an artefact generated by a language model that is imitating the form of a well-written argument, without any of the content. Any of these things could be responsible for making a piece of writing hard to interpret and forcing us to re-re-read.

What Makes Text Meaningful?

Under this framing, if a piece of text is meaningful to a reader, it doesn’t really matter how that text came into being: whether it was human-written, AI-generated, or formed by some ants in the dirt. This is starting to get into philosophical territory; since I don’t have a background in philosophy, I’ll just plainly state the issue that arises for me here.5

This “ants in the dirt” example that I linked to is from Hilary Putnam’s 1981 book, Reason, Truth, and History. I learned about it from Matthew Mandelkern and Tal Linzen’s 2024 article, “Do Language Models’ Words Refer?”, who explain it as such:

Suppose that, at a picnic, you observe ants wending through the sand in a surprising pattern, which closely resembles the English sentence “Peano proved that arithmetic is incomplete”. At the same time, you get a text message from Luke, who is taking a logic class. He writes, “Peano proved that arithmetic is incomplete”.

Intuitively, the two cases are very different, despite involving physically similar patterns. The ants’ patterns do not say anything; they just happen to have formed patterns which resemble meaningful words. Of course, you can interpret the pattern, just as you can interpret an eagle’s flight as an auspicious augur; but these are interpretations you overlay on a natural pattern, not meanings intrinsic to the patterns themselves. By contrast, Luke’s words mean something definite on their own (regardless of whether you or anyone else interprets them): namely, that Peano proved that arithmetic is incomplete. What Luke said is false: it was Gödel who proved incompleteness. But Luke said something, whereas the ants didn’t say anything at all.

Because of everything we just talked about, I disagree with Mandelkern and Linzen’s argument: I don’t think that there is any real difference between the ant-spelled and human-written text, at least in terms of the meaningfulness of that text. If we apply our “recipe metaphor” to this example, then the meaning that arises in our minds when we read “Peano proved that arithmetic is incomplete” is the same for Luke’s message and for the ants in the dirt. In both scenarios, the string “Peano proved that arithmetic is incomplete” induces the exact same thought in our head (apart from non-linguistic concerns, like “why is Luke texting me this?” or “how the hell did these ants happen to spell out an entire sentence?”). But crucially, this meaning is not “intrinsic to the patterns themselves”—it arises only when we see and interpret those patterns. And if someone else were to see the exact same patterns, the meaning that they would derive in their heads would always be slightly different.

This is what confuses me about debates on whether LLM-generated text is “truly meaningful.” If I read a sentence that causes me to have a particular thought, then I have made meaning from that sentence, and so the sentence is meaningful (to me). It used to be that LLM-generated text was hard to interpret, which meant that most of the time, it was not meaningful—unless you were a poor annotator like me, whose job it was to try very hard to interpret horrible things like “It’s all just the right amount of subtlety in male porn, and the amount of subtlety you can detect is simply astounding." But now, LLM-generated text is so good that the majority of it is meaningful to most people almost all of the time.

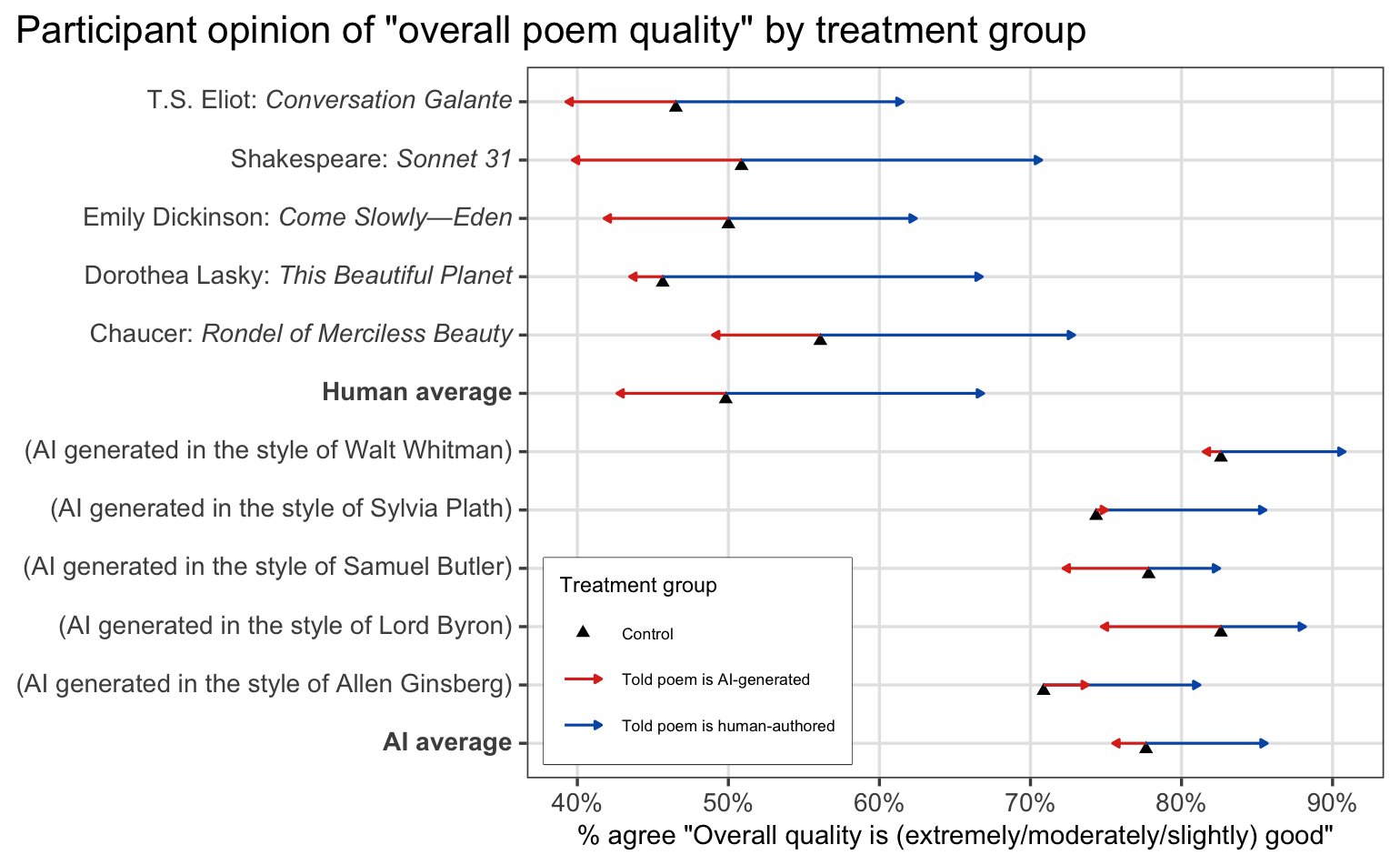

To me, the difference between Luke’s text and the ants’ sentence is in the non-linguistic considerations that arise when reading both messages. If you really saw something written in the sand by ants, you would know that this message was not “intentional,” and would therefore put less stock in whatever idea it triggers in your mind. (Unless you were superstitious and took the message as a sign, which maybe you should; seeing that for real would be crazy.) But if you knew that a piece of text came from a person, you would probably try harder to understand it, even if it seemed strange and meaningless at first. This reminds me of a recent study on human ratings of AI poetry: Colin Fraser on Twitter made a fascinating visualization of their data showing that ratings of poem quality for human-written poems are lower than ratings for AI-generated poetry—unless people are told that a poem was written by a human, which gives a massive jump in perceived quality (the blue arrows below).

It seems that participants in this study are rating poem quality based in large part on the meaningfulness of the text. For example, one subject rated an AI-generated poem as human-written because it “contained a lot of human experiences.” One subject, when asked to explain why they judged “Promised Years” by Dorothea Lasky as AI-generated, said that “the poem seems like it doesn’t have a clear idea.” If this respondent was told that the poem was written by a human, I wonder whether they would be willing to spend a bit more time and effort trying to interpret what Lasky was trying to say, rather than dismissing it as AI-generated.

I think that this poetry example serves as a nice foil to the ants-in-the-sand argument, because it highlights that the perceived meaningfulness of a piece of text has a lot to do with our perceptions of where the text came from. These perceptions determine how willing we are to spend time trying to understand a work: if we believe that a piece of text is human-written, we may spend a lot more time trying to interpret and understand it.6 So maybe this is why “Peano proved that arithmetic was incomplete” feels so different coming from ants in the sand, rather than coming from a trusted friend: if we know (or think we know) that something was written by a human, it changes the way that we approach interpretation of that text.

What if this AI Paper Was Actually Good?

There have been lots of infamous examples throughout the decades of people writing hoax papers that have made it past peer review. What’s interesting about these cases is that theoretically, it might be possible for a hoaxer to write a paper that they believe to be nonsense, but that, when interpreted by another person in the field, actually says something profound or interesting. Now that we are apparently letting LLMs write entire papers for us, this seems even more likely to happen. Unlike the hoax papers, the AI is at least “trying” to write something good. So, what if this particular AI-written paper had actually offered a truly profound breakthrough or insight?

It would be interesting if, one day, an LLM does actually write a paper that says something new and profound. Maybe it would be just as opaquely written as the above ZKML paper, requiring many human augurs to spend countless hours interpreting and deriving insights from the work. Hopefully this doesn’t happen: if such a profound AI paper did exist, I doubt that anyone would bother taking the time to understand it; it would probably get lost in a sea of nonsense papers. But if we did take the time to read such a paper, then those novel insights wouldn’t have come from an LLM—they would have come from us, the readers.

Discussions with David Atkinson and Andy Arditi back in November inspired a lot of the ideas that ended up here. Thanks to Adrian Chang for continual feedback on drafts of this post. Plus, thank you to Si Wu for recommending the book “Metaphors We Live By” to me, and all of the above for extra comments at the end.

Of course, the right thing to do in this situation would always be to ask for the paper to be reassigned, or review to the best of your ability with low confidence; if a paper is that hard to understand, it probably shouldn’t get published anyway. But a willingness to call BS seems to be a combination of seniority and personality. ↩︎

I learned about this idea from George Lakoff and Mark Johnson’s book, Metaphors We Live By, published in 1980. Thank you to Si Wu for recommending this book to me! ↩︎

Maybe the world would look something like the Human Instrumentality Project from Evangelion. ↩︎

Reddy’s name for this is actually the “toolmakers paradigm,” but since the way I think about it might not match his original essay exactly, I won’t use his term in this post. ↩︎

If you have a philosophy background and are interested in talking about this, please reach out! This has been bothering me a lot. ↩︎

If it is written by someone well-respected like Derrida, we would maybe spend even more time. ↩︎