Notes on Geometry Papers

Not All LM Features are 1D Linear (Engels et al., 2024)

[Paper, Video] - They’re basically trying to figure out how to decompose hidden states into sums of different functions of the input (features). So for example, you might have a 1-dimensional representation of an integer value 3, added to an n-dimensional representation of the language semantics of “three,” etc.

When you’re doing this, there’s a problem: how do you know whether a multi-dimensional feature you’ve found is “atomic”, or whether it’s actually possible to further decompose it into other sub-features?

Reducibility

To figure this out, they formally define reducible features—which crucially we don’t actually want to count as a good/valid multi-dimensional feature. So for a given multi-dimensional feature $\bf f$ (defined as a function that maps from inputs to some $d_f$-dimensional subspace), can it actually be “broken down” (e.g. latitude and longitude)?

They come up with two metrics to see if this is approximately true:

- $S(f)$ - Separability index. For all possible ways to break down a feature into $\bf a$ and $\bf b$, what is the minimum mutual information $I(\textbf{a}, \textbf{b})$? For example, a multidimensional Gaussian will not actually have mutual information between subfeatures if you choose the right axes. Higher = harder to separate.

- $M_\epsilon(f)$ - $\epsilon$-mixture index. Across all the token positions, can we pick a special vector $\bf v$ for which the feature can be projected near zero pretty often? (in practice, this is something like less than $\epsilon$ * standard deviation rather than zero). If you can find a vector $\bf v$ and offset $c$ so that $\textbf{v} \cdot \textbf{f(t)} + c$ is small for lots of token positions, then that means that in all of those cases that direction in the feature space wasn’t really being used. Of course, $\bf v$ has to be within the subspace $\mathbb{R}^{d_f}$, because otherwise you could easily find a vector that’s orthogonal to $\mathbb{R}^{d_f}$ and zeros out everything. Higher = easier to separate.

Concrete-ish example of mixture index

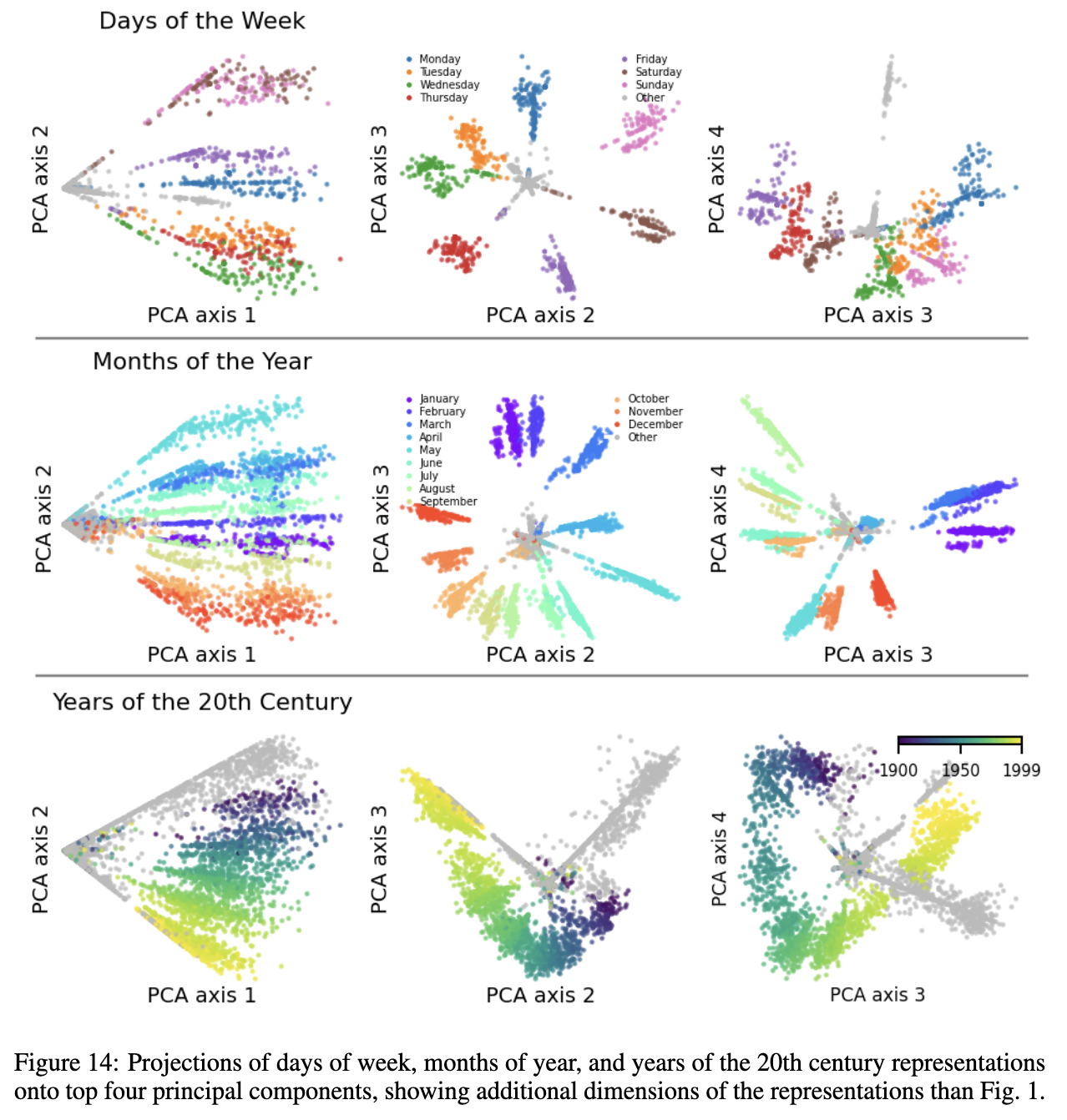

Let's say your multi-dimensional feature $\bf f$ was dimension $d_f=2$ but to your dismay it was actually a mixture of two features, $\bf e_1$ and $\bf e_2$. For 60% of the token positions where the feature is active, it's using mostly $\bf e_1$, and for the other 40% it's using mostly $\bf e_2$. In such a case, you could choose $\bf v=e_2$ and get a zero dot product for 60% of tokens and one dot product for the other 40%, resulting in a score of around 0.60. This is pretty high, and it indicates that this so-called "multi-dimensional feature" is actually just a combination of sub-features represented by $\bf e_1$ and $\bf e_2$.In practice, $S(f)$ scores for GPT-2 features are mostly less than 0.2 (aka, most features are pretty separable), and $M_\epsilon(f)$ features are quite high, mostly bigger than 0.4 (aka, most features are pretty much mixtures). They use these scores to argue that their day-of-week features, since they have high $S(f)$ and low $M_\epsilon(f)$, are irreducible multi-dimensional features.

Going from SAE to Multi-Dim Features

If $\bf D$ is the decoder matrix of the SAE containing all of the output features, then to cluster features together, they take the cosine similarity between all decoder vectors and prune away cosine similarities below a threshold $T$. By construction these clusters will be “$T$-orthogonal” (i.e. if $T=0$ then they’re truly orthogonal).

If the SAE is good at reconstructing, then when a multi-dimensional non-reducible feature $\bf f$ is active, they claim that one of these cosine-similar clusters will be equal to f. This is not super obvious. Naively, you’d think it’d be the opposite—that if $\bf f$ was a 2D feature that was properly reconstructed by the SAE, the SAE would have learned two orthogonal decoder vectors that span the space (and those would have close to zero cosine similarity). But if $\bf f$ is truly a multi-dimensional feature, it would never make sense to separate out these two features; then the SAE would get penalized by always having both features active whenever it needs to reconstruct $\bf f$. So instead, they guess that the SAE would learn a bunch of cosine-similar things that are all in $\bf f$ (intuitively, maybe this would be like learning separate “Monday”, “Tuesday”, “Wednesday” features).

So what they do is:

- Cluster all the SAE decoder vectors using this thresholding thing

- To analyze a cluster, get cluster-specific reconstructions of all hidden states $\textbf{x}_{i,l}$.

- Analyze that cluster’s representations across a bunch of hidden states by looking at PCA projections, or running $S(f)$ and $M_\epsilon(f)$

Two important details:

- In order to calculate these scores, they actually first calculate the PCA directions over the reconstructed activations, and then project onto PCA components 1-2, 2-3, 3-4, 4-5, averaging the separability/mixture over each of these planes.

- This process implicitly filters for datapoints that are relevant for this cluster/feature. In step (2), if none of the cluster’s features are active for a particular hidden state $\textbf{x}_{i,l}$, it is not included in the analysis. In the case of a days-of-the-week feature, the PCAs will of course look pretty nice, since the biggest variation between a bunch of weekday vectors will almost surely be information about weekday.

Another cool thing is that they show that these features are actually cones, where the first principal component seems to be intensity of weekday-ness, perhaps.

Intervening on Circles

While they do try intervening on the subspace found by the SAE, they get slightly better results by training probes to find good subspaces at each layer. Specifically, they

- Take the top-$k$ principal component directions of hidden states at the “Monday” position (pretty sure this position) across all the prompts and project onto there first.

- Then train a linear probe $\bf P$ in that space that maps from $k$ to 2 dimensions, trained to correspond to circle($\alpha$) – e.g. for weekdays circle$(\alpha)=[\cos(2\pi\alpha/7), \sin(2\pi\alpha/7)]$.

- To intervene on “Monday” and make it look like “Wednesday”, they just discard “Monday.” I am confused about how exactly this intervention works, because their Equation 6 seems wrong (you can’t calculate circle$(\alpha_{j’}) - \overline{x_{i,l}}$ directly because they are different dimensions). Equation 7 doesn’t clarify, it seems to have a missing parenthesis.

Josh Engels mentions in the talk that the intervention only works if you ablate out everything else that’s not in the PCA; I’m not exactly sure what he means here, probably the fact that they have to mean-ablate everything by using $\overline{x_{i,l}}$ instead of the base activation.

Generic Ideas/Takeaways

- How does the model actually use these circular representations to calculate the answer?

- Some of these facts must be piecewise memorized as well (e.g. Saturday is 1 day after Friday is almost surely memorized) – probably why they have to ablate all other weekday information.

- Presumably lots of weekday embedding information is unrelated to circles – if you rotated within the circle subspace for tasks like “What holidays are typically on [Thursday]?” or “What letter does [Thursday] start with?” then you’d probably see it doesn’t affect anything.

- It still worries me to think about multiple circles happening at once. If you have six orthogonal 2D circles, could that just be some alternate formulation of an n-dimensional subspace?

When Models Manipulate Manifolds / Linebreaks (Gurnee et al., 2025)

Line snaking through a subspace

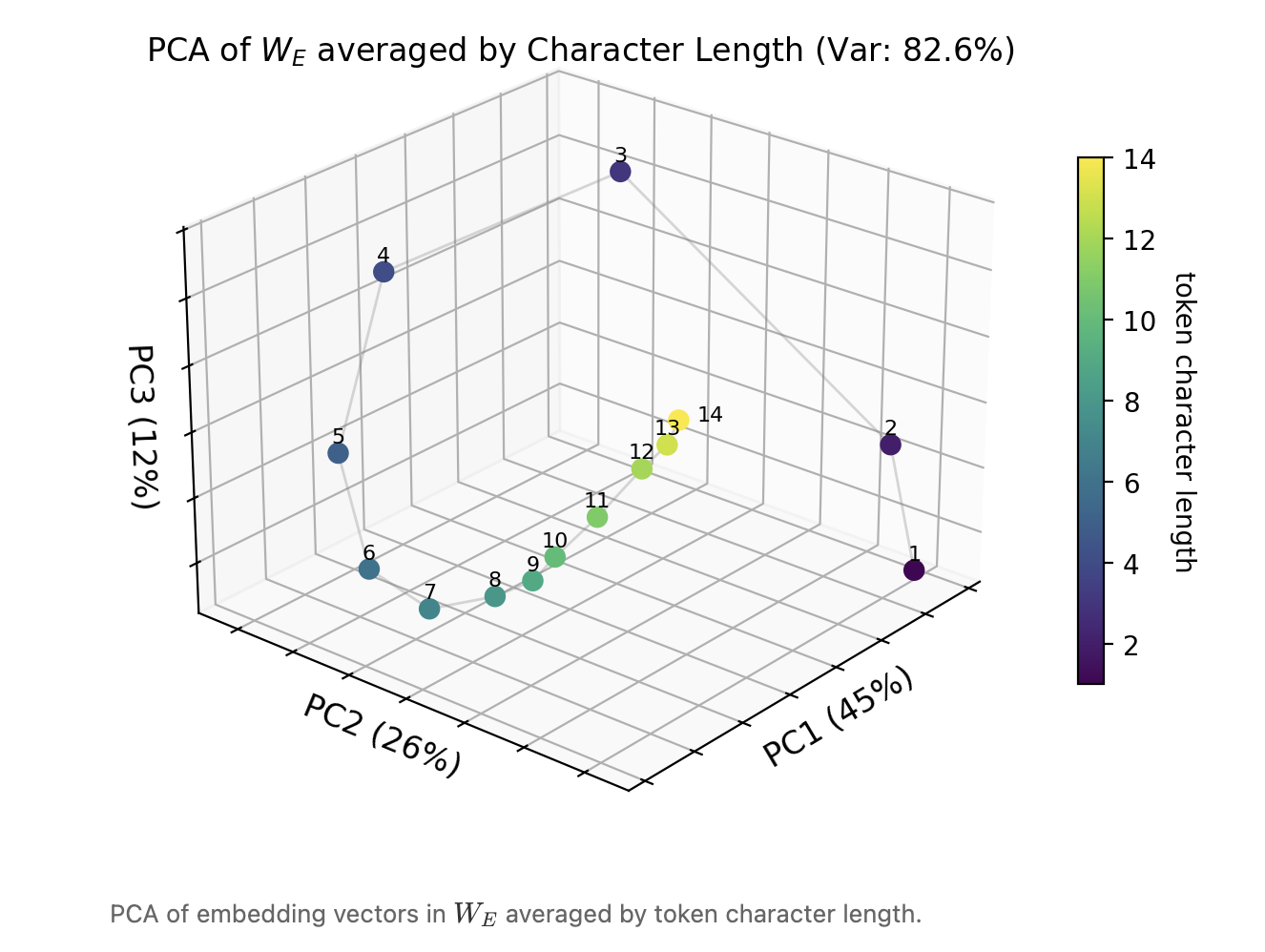

They find 1-dimensional feature manifolds embedded in low-dimensional subspaces for: num. characters in a token, num. characters in current line, overall line width constraint, num characters remaining in the current line.

- It wouldn’t really make sense to dedicate an entire 1D subspace to num characters in current line, because then you’re wasting that entire dimension if you’re in a doc that doesn’t have linebreaks. This is really strong evidence for superposition; as they note, a ring structure implies that there is superposition/interference in that representation.

They find a bunch of features that activate on a range of given line widths. Since two are usually active at a time, they imagine a curve connecting all these features. If they take PCA across 150 different line width averages for Layer 2, they find a 6-dimensional subspace that explains 95% of the variance across line width averages. They can also reconstruct the activations only using the SAE features above, and the curves track each other fairly closely.

- This is really interesting because there is no human-intuitive reason why line widths would have to be represented as a curve, right? Unless there was something about a 60-length line that nicely parallels a 30-length line? This really might be an artifact of superposition, because we don’t want to use up an entire dimension, so we snake it around like so; probably because you’re unlikely to confuse 60 and 30 anyway(?)

- Q: do all of their averaged-line-width features come from tokens within documents with a max line width of 150, or do they come from different documents with different max line widths?

- If we were trying to find this using some geometric DAS, why would we assume we’re looking for a curved manifold? Or, how would we figure out what kind of curves we might be looking for? This seems like something someone who’s good at math could figure out

“Ringing” plots

150-way logistic regression: basically just a bunch of model_dim vectors each individually trained to activate for e.g. a 50 char line, 51 char, etc. I misunderstood because of their language: the precise definition of “logistic regression” is binary classification with a single vector and a sigmoid activation function, but if you look closer they actually do multinomial logistic regression (“as a 150-way multiclass classification problem”). In other words, they have a probe $P\in\mathbb{R}^{(150,d)}$ and then calculate cross-entropy loss with $\text{softmax}(Px)$ where $x$ is a d-dimensional hidden state. So this is actually very similar to approaches I’ve used–the difference is that they analyze all of the rows of this resulting probe in interesting ways.

Anyway, if they take all these guys and do PCA, the top 6 components capture 82% of the variance of these vectors. You can just plot the behavior of each of these logistic regression probes d-dimensional probe rows on a heatmap, and see that the diagonal is quite fuzzy. But you also see that there is some small off-diagonal “ringing” in their predictions as well (which also occurs if you take cosine sim. between all the mean vectors, or the probe vectors).

- A very fuzzy intuition for this is that if you have some representation of line width that snakes around within a subspace back onto itself, as well as a logistic regression probe vector that’s trained to have a high dot product with lines of a particular length, then it wouldn’t just slightly activate for adjacent line widths but also for areas near it on the spiral. (This is basically the intuition in their toy example.)

Math details for their toy model: let’s say we want 150 vectors that are all somewhat similar to their neighbors but orthogonal to everything else. They define the cosine similarity matrix $X$ for this toy setting as a “circulant matrix” where basically you just have the row [1, 0.5, 0, …] permuted to the right in every row to create a fuzzy diagonal. If you take a 5-rank approximation of it using the eigendecomposition of $X$, then you get the same “ringing” pattern. Note: it is nice to just look at the cosine similarity matrix here instead of trying to think of a familiar shape in 150 or 5 dimensions.

Probably the reason why they define $X$ to be circulant is because of its connection to Fourier transforms. Multiplying by a circulant matrix implements a convolution, which is just multiplication in Fourier space; this means that circulant matrices have eigenvectors that are Fourier modes (i.e., fundamental waves). So this approximation they were doing is equivalent to truncating the less-important Fourier coefficients for $X$.

Since this toy Fourier approximation looks so much like their real-life ringing example, they wonder whether the line width stuff in the real LLM is constructed via Fourier features. They say you can’t have just any generic low-dimensional embedding of a high-dimensional circle that slides along itself via a linear transform, which I buy. In the footnote they have this derivation about how this particular circulant matrix is built out of Fourier features, and show that because of this fact they are able to get a transformation on this structure that “slides it along itself.” For the actual character count curve, they find that Fourier approximations are pretty good at explaining the variance compared to ceiling (PCA).

Circulant Matrix Notes

If you have a permutation $\rho$ that maps $e_i \mapsto e_{i+1}$, then since $X$ is circulant, this permutation "doesn't change it"; i.e., if we define $P_\rho$ as the matrix that implements our permutation, then $P_\rho X P_\rho^{-1} = X$. This gives us commutativity, $P_\rho X = XP_\rho$. Then if you have an eigenvector for $Xv = \lambda v$, then $P_\rho v$ is also in the eigenspace, since $P_\rho Xv=P_\rho\lambda v$ so $X(P_\rho v) = \lambda (P_\rho v)$. I'm still not clear on this last step: apparently if permuting eigenvectors leaves them in the eigenspace, then the permutation operation will work just as well in the low dimensional top-$k$ eigenvectors; thus, we have a linear map that operates on the projected-down manifold as well.Manipulation of Manifolds

All this stuff before was looking at “character count,” the number of characters that there are so far for some arbitrary token. Now, they train probes for “line width,” which is different for each document and specifically at the newline tokens.

They find a head that outputs a “boundary detection feature.” The hypothesis here is that its query would be the character count at the current token, and the keys would allow the head to match its “current chars” query to any previous newlines. So they have a bunch of probes that can identify “current chars” and “line width” features, which appear to be aligned if they take the joint PCA and visualize in 3D. Following their hypothesis, if they multiply the “current char” probes through the $W_q$ matrix, and the “line width” probes through the $W_k$ matrix, they see that the two manifolds are twisted against each other so that if we’re at “character count of 42” then we’ll activate the most for “line width of 46”.

- Probably unlikely that the distribution of line widths in real life is so uniform… interesting that the learned algorithm is so general.

- Cosine similarity heatmaps within the QK subspace show more “ringing”. Let’s say the current chars are at 38, then the head would attend heavily to a newline with width 40, but also kind of lightly to 20 as well.

- I wish we could know how big their model is, since it’s interesting that the model has several boundary heads. I wonder what % of its overall heads those take up. Also, the idea is that the boundary heads output information about how many characters are remaining as well as, presumably, whatever the separator token will be through the OV circuit. I’m not sure exactly how that would work.

Is the next token too long?

There’s SAE features that seem to activate only if the next token will be too long (and upweight newline), and also features that activate if the next token is short, downweighting newline. How does the model combine the next-token prediction with the detected boundary?

They calculate the mean over all the hidden states where the next token is $j$ characters long, and the mean over all states where there are only $i$ characters remaining. When you take the PCA of these mean vectors together, they look like two kind of orthogonal-ish curves. If you sum together any two points on the curve, that’s like saying, “there are $i$ characters remaining and I want to predict a $j$-character token.” The way these curves are arranged makes it simple to draw a plane where $i-j=0$.

- Do they consider that the model doesn’t actually predict one next token, but a distribution over future tokens? How exactly does that fit in here?

- “This sum is principled because both sets of vectors are marginalized data means, so collectively have the mean of the data, which we center to be 0.” Not exactly sure what the concern would be here?

How do heads actually calculate num. characters in a line?

Interestingly, if you train more little probes, one for each possible token length, you can see that they form a rippled circle. Again, funny why it would need to be a circle, but this explains 70% of the variance.

Apparently after layer 0 there’s already rough probe accuracies for current # of characters at a given token position. They don’t really explain how they find particular heads that are responsible for building up this information. The general vibe is that the QK circuit uses the previous newline as an attention sink and then smears the rest of its attn across subsequent tokens, whereas the OV circuit somehow combines an estimate based on avg. token length (4 chars) with “corrections” to each token based on the embedding-level information above.

Note on “taking PCA of probe”

I think that taking the SVD of the (n_classes, model_dim) probe $P$ from above is actually the same as doing PCA on the probe rows, if the mean of these rows is close to zero.

If you want to do PCA on the rows of $P$, then we can construct a matrix $X=P^T$ that has all of these row vectors as data points arranged in columns. (This is just a thing I’m doing so I don’t have to keep transposing $P$). For PCA you’d take the SVD/eigendecomp (basically the same for symmetric matrices) of $XX^T=Q\Lambda Q^{-1}$, assuming that the mean of the rows of $P$ is centered at 0. For SVD you have $X=U\Sigma V^T$. $$(U\Sigma V^T)(U\Sigma V^T)^T= Q\Lambda Q^{-1}$$ $$U\Sigma V^TV\Sigma U^T= Q\Lambda Q^{-1}$$ $$U\Sigma \Sigma U^T= Q\Lambda Q^{-1}$$ therefore $U$, the left singular vectors of $X$, are the same as the principal components of a PCA ran on the rows of $P$. The shape of $XX^T$ would be (model_dim, model_dim), and $U$ would be (model_dim, model_dim), but only at most 150 of those columns would actually be used.

Since we defined $X=P^T$ then it’s actually $V\Sigma U^T = P$ and thus $U$ is really the right singular vectors of our probe. Aka, these are the vectors that we rotate the residual stream space onto before zero-ing out $d-150$ of the model dimensions (or more, if it’s low-rank). We could also call them the “SVD input space” basis vectors; vectors that define which part of the residual stream is most important for this probe to make its decisions.

“The top 3 principal components of all the 150 logistic regression vectors” is actually the same as “the top 3 input space singular vectors”. This means that if we had the probe they had, and took the SVD, the singular values would drop off really quickly, I think.

Also, if we wanted to get the same plots as them after taking the SVD, the key thing to do would be to project all of the rows of the original probe $P$ onto the first three singular vectors on the right side of the SVD of $P$. This is quite intuitive, because if the probe has found a bunch of vectors in the residual stream that have a high dot product with a particular character count, then they should probably make sense projected onto the most important singular vectors for probing out that character count. But it’s also weird and circular.

I think that the “taking the PCA of all of these logistic probes” framing is quite nice and maybe more intuitive than what I’ve written here.